Argues that science can, and should, be an authority on moral issues, shaping human values and setting out what constitutes a good life. Harris challenges the traditional boundary between science and morality, proposing that scientific understanding of the human mind can lead to more objective and rational bases for discussing morality, ethics, and human well-being.

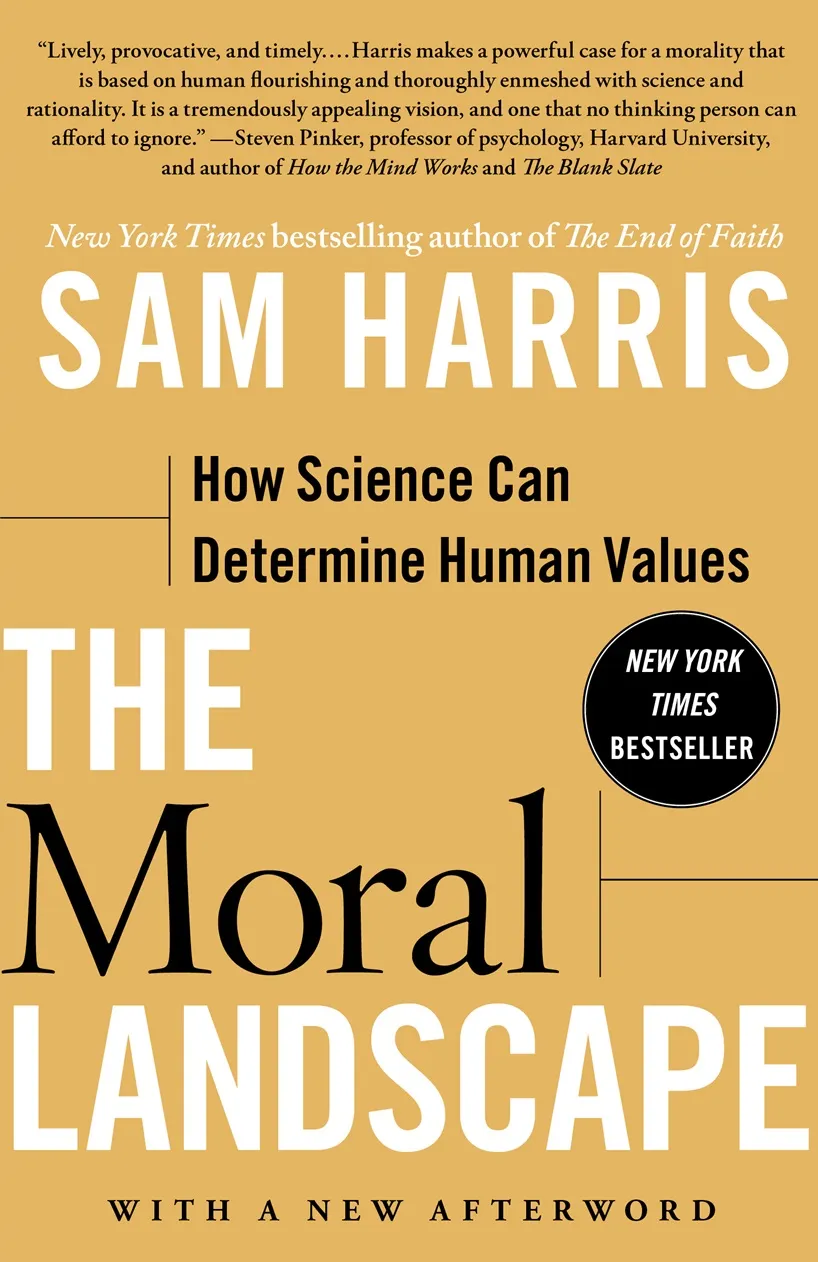

"The Moral Landscape: How Science Can Determine Human Values" by Sam Harris is a monumental attack on a common belief: that science cannot make statements about morality because it belongs to a different sphere. The author impressively demonstrates the opposite. He argues convincingly why moral principles should be based on scientific knowledge rather than historically grown religions or ideologies.

Sam Harris is a neuroscientist, philosopher, and an atheist thinker who has made a name for himself with his previous books such as "The End of Faith" and "Letter to a Christian Nation" as a warner against religious dogmatism and fanaticism.

The book is a response to criticism of the author's first books. This criticism can be summarized as the belief that science cannot make statements about morality. This assumption is deeply rooted in society and is increasingly seen as one of the most important justifications for the existence and relevance of religious faith. However, the book is not just about not leaving the moral interpretation to religions and ideologies, but also about refuting moral relativism. In doing so, the author manages to turn both political fringes against him: the religious right and the moral relativist left heavily criticize the author.

Even in our modern, liberal society, the view of science and morality as completely separate spheres is still often held. For example, evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould speaks of non-overlapping domains of application for religion and science. He concludes from this that the methods of one are not suitable for studying the other domain and vice versa. Harris counters this view by arguing that science offers both possibilities to compare different moral concepts and to make statements about moral goals. He convincingly explains how morality can be measured: It forms the foundation of a society's coexistence, therefore its effects can be scientifically studied very well. This allows us to show which morality is better and which is worse. The author illustrates this by contrasting two maximally different lives of fictional persons: Person 1 is a woman living in a totalitarian theocracy. The prevailing morality there degrades every woman to the property of her spouse, a fact that her husband mercilessly exploits for regular violence, abuse, and rape. Person 2 is a woman in a liberal democracy who, thanks to the diverse opportunities, was able to develop professionally and personally and lives with her partner in harmony and on an equal footing. In this example, the various scientific disciplines (neurobiology, psychology, sociology, medicine, ...) very clearly indicate which morality leads to a better outcome and which one to a worse. With increasing understanding, we can also make better distinctions in less extreme cases and thus objectively compare different moral concepts with each other.

The author also addresses the foundation of morality: Since values and morality can logically only spring from an intelligent being with reason, he argues for using the well-being of those intelligent beings as a fundamental decision criterion. This can be measured and explained better and better, especially with the steady progress of neurobiology, even though research still has a lot of potential for improvement here. In my opinion, this argumentation could have been a bit more extensive and detailed in the book. Nevertheless, this origin of morality is very well justifiable with the current state of science and thus much more convincing than historically grown moral concepts that ultimately rely on indirect traditions from antiquity.

Scientific findings must be reproducible and verifiable, therefore they are by definition universal and not in the eye of the beholder. If morality, as argued above, must be viewed scientifically, the author concludes that there can be no different equally correct moral concepts. He compares this to the fact that there is also no Christian mathematics, no Islamic biology, and no communist physics. Something cannot be right or true just because many people have believed or done it for a long time. Therefore, the author condemns - in my opinion, quite rightly - any form of moral relativism. Norms and actions should not be evaluated differently just because the cultural and historical causes are different. This can be illustrated with the following thought experiment: If only a single person in the world came up with the idea of cutting off a part of the skin on the penis of male babies, the only question would be how severely this person should be punished. However, if many people have been doing it for a long time, it is okay and should be respected. As in any scientific discipline, personal conviction and belief are therefore not sufficient as arguments. The author thus pleads for not giving these voices any space in the discourse on morality, just as we ignore unscientific opinions in chemistry or astronomy. This would represent a stark contrast to the status quo, in which ideological and religious fanatics not only have a voice but often even carry more weight than well-founded scientific arguments.

Overall, a highly recommendable book on a controversial but extremely important topic. In addition to the basic statements presented above, the author offers many interesting insights into the connections between neurobiology and morality. "The Moral Landscape" appealed to me personally mainly because it addresses and clearly expresses much of what corresponds to my intuitive understanding of morality: We can and must view morality scientifically - therefore, ultimately, there can be no historically or religiously shaped differences. If we move the moral discourse into scientific spheres, we can finally bid farewell to many energy-sapping debates of the present: We could deal with important problems like climate change and wouldn't have to endlessly listen to intellectual quacks about why women should have fewer rights or why people with different sexualities shouldn't be allowed to marry.

To conclude, here's an interesting thought from the author: Moral progress means that our descendants will be as disappointed with our morality as we are with the moral concepts of our ancestors. I think if we take the message of "The Moral Landscape" to heart, we could be the first generation whose descendants no longer perceive our moral concepts as outdated and unjust.